Interviewing Max Harrison in Marylebone is a bit like interviewing Elmo on Sesame Street. The maître d’ of Chiltern Firehouse is the area’s spirit animal and local celebrity, its smiling face and welcoming embrace. Every five minutes or so during our conversation – sitting outside a little deli on Chiltern Street on a sunny Thursday in October – a wellwisher or pal comes up to say hello or “Oi” or “Here he is”. A writer, a shopkeeper, a financier, a socialite, a barman.

All of them, eventually, ask him a form of the same question: the one that’s bugged the chattering classes since Valentine’s Day, when London’s most enigmatic hotel – the grand, red-bricked Victorian firehouse – in a stunning moment of irony caught fire itself. “When will it reopen?”, they all ask. Which is another way of saying: “When can we see you again?”

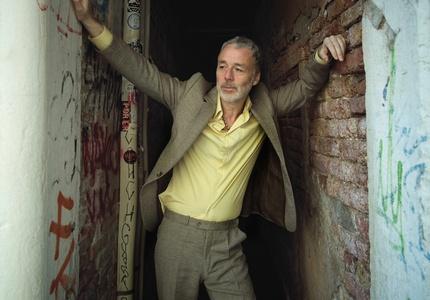

Harrison has become synonymous with Chiltern Firehouse. His is the face – and the hair, and the blazer – that most often greets you at the lectern in the burbling courtyard at its front. He joined the hotel a few months after it opened in 2014 and has grown in stature in the decade or so since. Around 2020, he gradually stopped wearing the mandated team uniform and began dressing more as himself – a “sexy, fly debonair” look, he says, with a touch of JFK– as well as dying his hair a suitable shade of brick red. “That’s the moment when I started changing from Max Harrison from Bethnal Green to Max Harrison of Chiltern Firehouse,” he says with a laugh. “The beloved comedy character and national treasure.”

As a young man, Harrison briefly went to drama school. “I was terrible,” he says. “But we did a clowning course. And the teacher said, ‘You’ve got to find your clown’ – which is the element of your personality that is elevated, that is turned up.” The hotel, Harrison says, “is like Disneyland. The real world doesn’t exist when you’re there. And this gives you a freedom to behave in a certain way – a jester’s privilege, perhaps.”

Some front-of-housers will tell you that the secret to the craft is “to get really good at recognising watches,” Harrison says, “because that will tell you who has the most money.” But what differentiates him “from the other girls” of London’s maître d’ mafia is that he believes the job is essentially a piece of prolonged nightly performance art. “I know it is a cliché to talk about the theatre of restaurants,” he says, but in this case, “it’s ultimately true”.

“But listen. If I behaved in Bethnal Green like I do at Chiltern Firehouse, I’d get beaten up.”

Max Harrison grew up in Bow, east London, “just off the Roman Road”. His parents “came from very working class backgrounds and were very left wing, working class people.”

In the mid-’90s, in the thick of the golden age of hip-hop, Harrison came to love rap music. “It had this very open aspiration – it was very unapologetically materialistic. And the only way that I could think of to rebel against my parents was by becoming this sort of hyper-capitalist,” he says, laughing. He started out working in retail, at John Lewis. “I had no ambition towards hospitality at all. My only ambition was to look cool in nightclubs and do everything that that involves.” A prototypical ‘club kid’ of the early noughties, “I saw social life as this game in which you are always just trying to get into the next room.”

But by the age of 28, the lifestyle started to wear on him. It was 2012, a time when his friends Pablo Flack, David Waddington and Clive Gregory, the founders of Bistrotheque in Hackney, were preparing to open their restaurant Hoi Polloi in the Ace Hotel, Shoreditch. “I’d never even thought about hospitality,” Harrison says. “They were like, ‘You can be a maître d.’’ And I had no idea what that was.” They told him it was just a case of talking to people, which he liked the sound of. He joined as a host, but on the opening night the much more senior maître d’ “had a freak out” and quit – and Harrison, on his very first day in hospitality, was promoted to the top job.

In 2014, he was invited to do a trial shift at Chiltern Firehouse. The hotel had opened in February that year in a barrage of flashbulbs and headlines – the clubbiest spot in London, despite not even being a club. In its opening weeks, founder André Balazs, the hotelier behind The Standard and a revitalised Chateau Marmont, estimated that the restaurant at the hotel was fielding more than 2000 calls a day. It was into this peculiar maelstrom that Harrison first arrived. “And it was really fucking fabulous,” he says. Paloma Faith, an old friend, happened to be dining that night, and shouted “Hire him!” to then-restaurant manager Ben Hesketh as he crossed the floor. A little later, he had an interview with Balazs. When the boss walked in, Harrison was reading a book from the Mapp and Lucia series by the 1920s society novelist EF Benson.

“André picked up the book and he said, ‘What’s that about?’ I said, ‘It’s about social snobbery in the English class system,” Harrison recalls. “And André said, ‘Well, that’s all you need to know,” and gave him the job on the spot.

Despite its reputation (especially in the early days) as a celebrity-filled hotspot – a sort of tabloid red rag of elites and decadence – Harrison believes part of the hotel’s success was a certain democracy. “It’s an understanding of how the people in the room elevate that room” – and that a proper mix of characters (out-of-towners and locals, old and young, rich and not-so-rich) is the key to a good atmosphere. “And to achieve that, you have to let people in.”

In the aftermath of the fire, one would hear gossip and declarations that such-and-such was “The new Chiltern Firehouse”.

“But no-one has done it,” Harrison says. “You can’t. You can’t replicate these individual people that work on this individual street that has its own ghosts and its own stories. You can’t copy that with a mood board.”

What will it be like when it returns? “It will be just as good, and better.”

This article first appeared in the second issue of Broadsheet London's magazine.